“Be very careful of people who celebrate purity…And that’s not even history, it’s just basic Harry Potter.”

-Vir Das, from his Netflix standup special, Landing

The American church, like America itself, is obsessed with sex. When I was growing up in the 90s and early 00s, Christian pop bands banged out odes to abstinence, Christian bookstores sold not just purity rings, but abstinence-themed books, journals, and magazines. There was even “Revolve,” a New Testament disguised as teen mag with “helpful” sidebars about why you should wear a t-shirt over your swimsuit and NEVER let a boy tickle you! My generation got the message loud and clear: the most important thing you can be as a young Christian woman is pure.

The Purity Movement was inescapable at that time. Pop stars from Brittney Spears to Jessica Simpson to the Jonas Brothers sported purity rings and proclaimed in MTV interviews, “I’m saving myself for marriage.” (Even the phrasing of that sentence strikes me now as it equates virginity with selfhood.) Church groups took to concerts, county fairs, and even public schools to pressure teens like me into signing abstinence pledge cards.

I gladly signed. Sex was dangerous; that had been drummed into me since before puberty. Sex was a fire that, if let out of the “fireplace” (heterosexual marriage) would destroy your life. Even the non-abstinence-based sex ed I received at public school focused on fear tactics: gory photos of STIs and graphic videos of childbirth. There was no talk of pleasure, consent, or developing an ethical framework for sex, just the all-caps message: DON’T DO IT.

I’m not writing this to lay blame on any one person. Purity Culture was not the fault of a particular youth pastor or one bad book: it was a set of norms implemented by many trusted authorities and reinforced by the media. It was every time a church mom called a girl’s outfit “slutty,” every accountability group that cajoled boys into promising not to masturbate, and every smirking comment about our future wedding nights.

My indoctrination was milder than many of my generation—my pastor avoided the awful object lessons prevalent at the time: that non-virgins were as worthwhile as used-up tape, as desirable as a rose stripped of its petals, and as disgusting as chewed gum. I didn’t even read the purity culture manifesto I Kissed Dating Goodbye. But Purity Culture was still the air I breathed; it was inescapable.

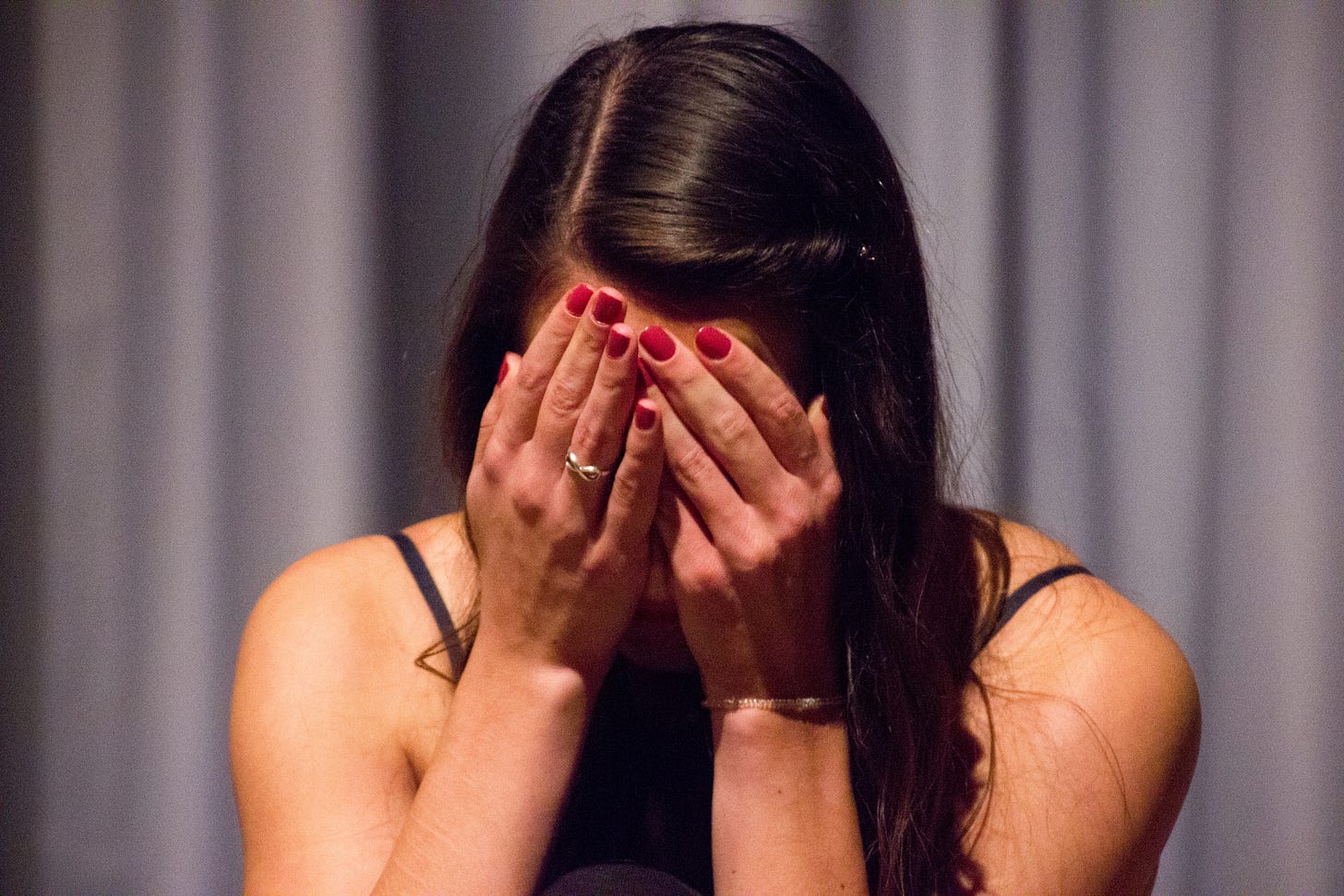

The cumulative effect of years’ worth of Purity Culture messaging was shame and paranoia. The girls at my Christian college were terrified of getting pregnant, despite the fact that they’d never had sex. Some went as far as routinely buying pregnancy tests—taking them was the only way to quell their obsessive anxiety. We talked about what we would do if a man tried to rape us. Would it be better to die than have our purity taken? Our churches never told us explicitly, “Virginity is your only value as a woman,” but, nonetheless, that was the message we received.

All this came back to me as I was reading Dr. Anna Lembke’s excellent book, Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in an Age of Indulgence. In her chapter on pro-social shame, Lembke explains that groups with strict, countercultural rules actually grow faster and are more successful than groups with a more relaxed attitude. Strict rules make it easier for the group to ferret out “free riders.” Soon the only people who remain are those who are deeply committed. “Club goods,” or shared benefits, are then bestowed upon these “worthy” group members.

Linda Kay Klein illustrates how purity plays out as a group-defining norm in her book, Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free:

“…I couldn’t always tell the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian. I saw both lie, both steal, both love, and both unselfishly give to others. But one tangible thing we could point to as evangelicals was that we didn’t have sex before marriage. Which is why, I believe, the threat of losing that so-called sexual purity seemed so grave. Were we to have sex outside of marriage, could we even call ourselves Christians anymore?”

She also goes on to point out that losing one’s virginity outside of marriage is considered the one sin that’s irreversible:

“After all, what other sin is said to fundamentally change you forever? You can be born again and have your slate wiped clean of lying, stealing, even murder…But sex outside of marriage is the only “sin” that I have ever heard described as changing you.”

All of this got me wondering whether this “pro-social” shame is the entire point of purity culture. Think about it: historically, there may have been protective reasons for not having sex before marriage, but things have radically changed. Our understandings of gender and relationships has evolved. Birth control and condoms revolutionized the consequences of sex. But the church’s line on abstinence is stuck in the Victorian age. Why? Pastors talk about “Biblical marriage” or “God’s plan for marriage” as if the Bible talks of June and Ward Cleaver rather than arranged marriages, polygamy, and women being forced to marry their rapists. It seems to me that this inflexible, top-down decree that all premarital sex is sinful smacks more of a commitment test than a helpful guideline.

For what it’s worth, I followed the advice of purity culture and remained a virgin until my wedding night. And? I have regrets about it! While I can appreciate that it was probably good that I had some counterweight to my raging teenage hormones, I do wish I’d explored my sexuality more before getting married. Beyond that, the emotional baggage of purity culture has taken a toll on both my relationship to my own body and my marriage.

So this month, I want to examine purity culture’s long-lasting effects on both individuals and society as a whole and how we can recover from the shame of it all. I want to nail down the messages of purity culture, both good and bad, and work towards a sexual ethic that honors myself and my partner. I’ve got some interviews lined up that I’m very excited about, and, as always, I’d love to hear your thoughts, either via email or in the comments.

Journal/Discussion Questions:

What messages did you absorb about sex as you grew up? In what ways was shame communicated to you about your body and sexual desires?

Do you have any questions for our purity culture experts? Please share!

What’s the worst metaphor an adult ever used to explain sex to you?

My mother was raised strict Catholic. I was baptised and confirmed in the Catholic church, but we weren't really regular attendees. When she and my father split, all the blame was placed on her, despite the fact that he was an active alcoholic. Her Catholic upbringing guided my sex education for sure, we rarely talked about sex and certainly never in the context of pleasure. Despite attending a Jesuit university, I spiritual, not religious. When I came time for those conversations with my own kids, i was very direct and pleasure was part of the discussion. My daughter was comfortable with the conversations, it made my son's skin crawl. I try to keep open communication with both. Not sure how well I succeeded with this particular topic, but I'm comfortable that I did better than my mom.

Great post, Katharine. A couple things I learned recently in studying about how the purity movement hijacked the early centuries of Christianity:

-When Jesus spoke of purity it likely wasn't about sex, but rather about single-mindedness. Being purely focused the way that gold is pure and without contaminants. He was saying be single-mindedly focused, purely focused, on the one thing that mattered.

-Paul (and many others) misinterpreted this and made it about celibacy. But note that when Paul talks about celibacy he never uses Jesus as an example of someone who was celibate. (I've been compiling the evidence that suggests Jesus very like "could" have had a wife or partner.) In the centuries after Paul the church only became more and more obsessed with sex. Talk about the shadow, right?

Not to mention that so many of the purity laws of the Old Testament were about the survival of the tribe. Back then the consequences of certain behaviours (even eating certain foods) likely had much higher consequences, such as transmission of diseases that weren't easily curable.