Let's Not Make "Budget Culture" a Thing, Okay?

On generosity, tithing, and intentional spending

It was on Virginia Sole-Smith’s podcast, Burnt Toast, that I heard the phrase, “Budgeting is diet culture for your money.” I nearly threw my phone across the room. (It wouldn’t have helped—Bluetooth headphones.) If that quote makes no sense to you, congratulations! How does it feel to not have a brain soaked in internet discourse? But seeing as the quote’s source, Dana Miranda, was featured on a widely shared Substack from Anne Helen Petersen last week, it feels important to talk about what, exactly, this anti-budget mindset gets wrong.

A few caveats: I am fans of both Petersen and was previously a fan of Sole-Smith (I’ve since rethought much of her approach.) I agree with Miranda that many “budget gurus” like Dave Ramsey are charlatans, and the idea that, by skipping a latte or two, most Millennials will be able to afford homes is laughable. The big issues preventing younger generations from building wealth and stability are stagnant wages and a massive shortage of housing.

But I disagree with much of Miranda’s mindset towards budgeting. As she said in the Substack:

“I call the dominant approach budget culture, because it’s rooted in the restriction and shame inherent in budgeting behavior. But, just like diet culture, it’s not about the act of budgeting; it’s about the cultural posture that makes budgeting seem like useful and necessary behavior.”

Calling something a “culture” seems to be having a moment. In some cases, this is a useful construction for calling out pervasive attitudes that contribute to larger societal issues, such as rape culture, purity culture, and diet culture. It’s a way of questioning the dominant paradigm, (i.e. the assumption that the “casting couch” was part of doing business in Hollywood is part of rape culture.)

But while there is a lot of media around the dos and don’ts of budgeting, is budget shame really the dominant cultural attitude towards money? While Miranda diagnoses our culture as being obsessed with greedily hoarding resources, I’d say a much bigger problem is a lack of intentionality with money, which we could call “Treat Yo Self Culture.”

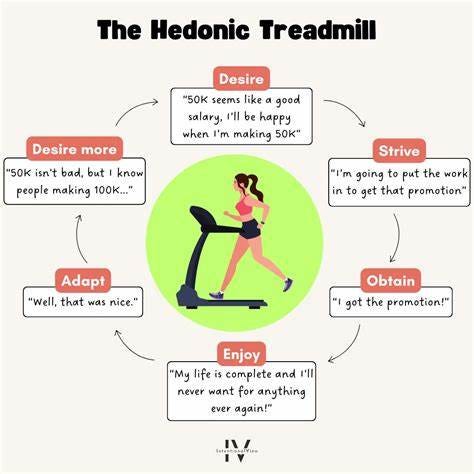

Don’t get me wrong, I love both Parks and Rec and the occasional l’il treat. But it’s funny how one little treat can turn into five and then become a habit rather than a treat. (*cough* Hedonic Treadmill *cough*)

The more I’ve talked with folks about money, the more I realize it’s actually uncommon to have a budget, or even to know how much money you’re spending on a given category such as groceries. When our culture is constantly pushing us to buy, buy, buy, resisting this onslaught of marketing means being intentional with our money.

And how do we set our intentions with our money? You’re not gonna like the answer!

keeping tabs on spending and

creating a budget

Tracking your spending is like emptying out your entire closet onto the bed only to realize you have three of the same sweater. The next time you’re at the mall reaching for another identical sweater, hopefully you’ll remember your closet. Facing up to exactly how much money you’re spending on take out, for example, can feel disheartening, but, contrary to Miranda, I don’t think it needs to be a shameful experience. Budgets are plans, and plans must be flexible. Sometimes you’ll go over, sometimes you’ll be under. That’s okay.

My husband and I sat down to do a money check-up last week. We spent A TON of money on travel last year—both of us took 40th birthday trips, plus we took a trip to the Grand Canyon and road tripped to visit family last summer. As we talked through the eye-watering sum, we decided that we would cut back a bit this year, but, overall, we’re happy to spend money traveling because it’s something we value. In fact, having money to travel was one thing we took into consideration when we bought a cheaper house than we could, technically, afford. It’s also one reason we share a single, 20-year-old car. For us, those are trade-offs worth making. And they wouldn’t happen without a budget.

One spending category that tends to be an afterthought is donating to charity. While there are a lot of things I criticize about the church, counterintuitively, I think the church mostly gets money right. During our stewardship campaigns, we heard messages about the good our money could do through giving to the church and were reminded that what we earned came, ultimately, from God.

Whether or not you believe in God, it’s humbling to remember your resources come not simply from your own hard work, but rather, a series of fortunate circumstances and community investments. Paying taxes and donating to charity are good ways to give back to these sources. So I think “tithing”—setting aside 10% of your net income to donate—makes a lot of sense.

For some people who are truly struggling, tithing may not be possible, but I think for the vast majority of us, dedicating 10% of our income to charity would help us cut back on wasteful habits and refocus our money on what’s important. Plus, it feels good!

I’m not saying budgeting is easy. It’s work. Getting started is hard. (All change is hard!) I’m fortunate enough that my husband is a spreadsheet nerd who takes on the lion’s share of the budgeting work. But regardless of who does it, I do believe that the hard work spent tracking, budgeting, reconciling the budget, and communicating with your partner/family about money pays huge dividends.

For you, what’s the most daunting part of budgeting? Where do you wish you spent less money? (For me, it’s random household gadgets, makeup, and clothes.) Where would you like to spend more? Do you have a long-term financial goal that could be helped by budgeting? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

BONUS MATERIALS:

there are a ton of great apps that automatically track your spending. We’ve liked the free version of Mint and YNAB, now we pay for the yearly subscription of YNAB. Forbes has a good roundup of others here.

need some anti-shopping motivation? Check out this new documentary on Netflix.

I haven’t read the article you refer to, but my issue with budgeting is primarily philosophical - it implicitly assumes scarcity, whereas I try to hold a philosophy of abundance.

I also have, as Christine described, “a reactionary response against anything that feels restrictive” and the word “discipline” sends me into shivers from having people “who knew what was best for me” try to push me, a square peg, into a round hole for most of my life.

I now seek what Carl Rogers calls “an internal locus of evaluation” - taking information from outside sources but not external judgments. (Easier said than done I’d add - very much a work in progress)

You mention what might be called “weaponised budgeting” as a means to shame millennials/genZ for suffering from the structural inequalities ingrained in the system, which I still overhear from some boomers, ironically sitting in coffee shops sipping their own lattes.

There is a subtlety between a hipsters avocado toast and the hedonic treadmill, and I think we need to be able to recognise that both unsustainable hedonic spending and strict budgeting are both scarcity based approaches to life.

I love YNAB and have been using it for maybe close to ten years? Their concept of “give every dollar a job” was an effective mindset shift away from the crystal ball style of budgeting future dollars that don’t exist yet. It’s been a super flexible tool through years of self employment and income fluctuations.

Having a budgeting mindset has also helped me in my work (creating project budgets) and running a small business (keeping track of lean profit margins).

That being said, budgeting and restrictive spending are often weaponized against people living on low incomes, as if poor people could rise out of poverty if they were simply more responsible and spent less. This leads to a privileged mindset of determining who deserves help.