“It happened to your body, it didn’t happen to you,” explains the matriarch of the Fletcher clan in Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s latest novel, Long Island Compromise. These words are meant to spare her son, Carl, further suffering after he survives a kidnapping attempt, but like dirt swept under a rug, trauma finds a way of leaking out. Over the course of the book, we see how this trauma pings and echoes through generations of the Fletcher clan. If it sounds like a bummer, don’t worry, it’s got plenty of Brodesser-Akner’s wealth-skewering raunchy humor. (God, I love her.)

For Carl Fletcher, as for many of us, facing our suffering is a scary thing, one that is discouraged by culture with its obsession with positivity and “getting closure.” Just move on is the message from many corners of culture, including churches. Too often churches focus on selling the image of Christ as victor over suffering, not as our fellow sufferer. Quieting talk about illness, pain, and trauma is another way that churches discourage embodiment.

Likewise, living in an age of astounding scientific advancement lends many to imagine we can conquer suffering once and for all. As I’ve written previously, human responses to suffering generally fall into three categories: fix it, forget it, or face it. In fact, the “Four Fs” of trauma response largely overlap with the first two responses:

It may be most beneficial for us to face our suffering like good little fully embodied stoics, but trauma complicates our ability to do so. Trauma is, by definition, completely overwhelming. Traumatic memories don’t even live in the same part of the brain as normal memories, which can make it hard for survivors to articulate what happened to them. Even if you can narrativize your experience, it might not help. While talking things through with a supportive person helps humans process most experiences, talking about trauma can trigger flashbacks and further overwhelm. Mindfulness exercises can, likewise, actually make trauma symptoms worse.

So what’s a person with trauma supposed to do? I want to live more embodied and be more present, but as someone recovering from Complex PTSD, my body is often a scary place to be. My feelings can be overwhelming, and on top of all that, there are the meta-feelings (that is feelings about those feelings) like, “you shouldn’t feel that way,” “I can’t believe you’re still stuck on that,” or the perennial PTSD favorite “what is wrong with you?”

How can people like us learn to be more embodied?

We need to ascend what Hillary L McBride refers to “the staircase of stress response”—that is, moving our bodies and minds towards safety. In her book,

The Wisdom of Your Body, she explains this way: imagine you’re hiking and you spot a cougar. Your first step may be to call for help (social engagement.) If that doesn’t work, you may try to run away from the cougar (mobilization.) If you can’t outrun the cougar, your body may involuntarily go limp (shutting down.) This system of stress response is largely involuntary, but we can train ourselves to go back up—to take action, ask for help, or to notice signs of safety around us.

Getting unstuck often involves working with a trauma therapist or support group. One example I’ve worked through with an EMDR therapist is flashbacks and triggers while setting the table for dinner. This was a stressful scenario for me growing up because by evening my mom was usually drunk and the dinner table was the site of a lot of family conflict. Even as an adult in my own home with my own family, the act of getting ready for dinner often triggered feelings of abandonment, anger, and fear. Once I understood why this was triggering, I could pause and breathe (mobilizing) and ask my husband and kids to help set the table (social engagement.) I could mindfully notice my surroundings to remind myself I wasn’t trapped in that old scenario anymore (safety.)

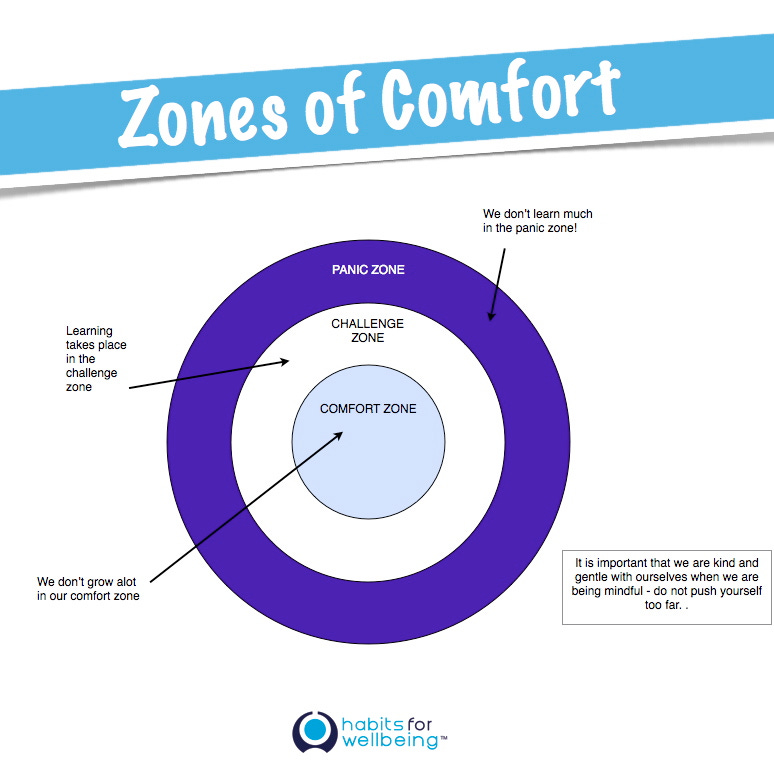

This safe and slow exposure to triggers is called “titration” or moving into “the challenge zone”—the space between comfort and panic. Discomfort is, unfortunately, part of growth, but we don’t want to push all the way into overwhelm.

It’s common to feel discomfort, pain, or resistance when getting started with embodiment exercises. This can feel like pain or tightness in a certain body part accompanied by intense emotions. When I recently tried one of McBride’s exercises, I felt a ball in my throat and heaviness in my chest—sensations I’ve come to recognize as grief. Often when I tune into my body, I notice fear and anger, which is very unpleasant! Noticing these sensations helps me understand my urge to stay busy and keep checking things off my to-do list (and getting that dopamine!) instead of staying present in my body and feeling all my long-ignored emotions. This worked out pretty well for me, socially, as our society loves self-sufficient doers. As McBride writes:

“In a societal context that celebrates bodily dissociation and mastery of physicality as a sign of maturity or status, the body’s natural desire to heal can be perceived as a threat. We take pride in pushing ourselves beyond our physical limits, reward workaholic employees for their commitment, praise people who eat restrictive diets for having enviable self-discipline, and celebrate ‘mind over matter’ as a sign of moral fortitude. Meanwhile we are suffering.”

But suppressed/ignored feelings don’t disappear. They can manifest in physical pain and inflammation and literally change our DNA. We are only beginning to understand the impact of trauma on epigenetics—research has shown experiences like genocide, war, and famine can impact even the grandchildren of survivors. This was brought home to recently when my son dropped a metal water bottle while my dad was over. We startled identically and I briefly wondered if our shared response was based, in part, to epigenetic changes due to my grandfather’s combat experience in World War Two. (Or maybe metal water bottles are just ungodly loud?)

But whether or not you are or plan to become a parent, we all deserve healing and wholeness. One of Jesus’ main activities during his time on earth was healing people. He didn’t question or blame people for what had happened to them, he didn’t charge them money (unlike many traveling healers of his time), he just healed them. Our demons may be frightening, but healing is possible, if we have the courage to face them.

In what part of your body do you primarily feel emotions? Is it your throat, guts, shoulders, someplace else? Also, is there a worse sound on earth than a metal water bottle hitting the floor? Let me know in the comments.

BONUS MATERIALS:

I carry emotional stress in my spine, right between my shoulder blades. And also in my hips. I find that if I can stretch these areas, and keep them flexible and open, my anxiety and nervous system becomes calmer.

I think I feel different types of emotions in different places. A deep sorrow rides in my hips. Fear rests heavily on my shoulders. Anxiety balls itself in my throat. Craving unmet lays across my chest. I think the beautiful thing is that joy balloons and can sort of be everywhere.

Great post, Katharine.