Is writing my job, or a hobby? This question haunts me. Am I not taking it seriously enough? Should I be doing more to sell myself, more to drive my own production? Should I spend more time hustling and trying to figure out the one weird trick that will make my follower growth EXPLODE and net me generous book deals? Where are my SMART goals??? How am I OPTIMIZING???

And part of me recognizes that the arts are, by and large, a pyramid scheme. Most of the professional writers I know earn a living primarily from teaching or coaching other writers, not from the pittance outlets are willing to pay for personal essays, articles, and even whole-ass books.

Even for those artists, who, like me, have married a partner with marketable skills, money makes things complicated. Financial security doesn’t preclude strife. Whose work is a higher priority? How to fairly divide the endless domestic and care tasks? With a husband who outearns me by an absolutely astonishing factor, it makes no financial sense for me to do anything except enable him to work more. Logically, I should become his servant, I should disappear completely into my role as wife and mother, which is what much of society deems appropriate anyway. Ideally, I should cease to have ambition or needs.

But my secret wish? Write a bestseller that turns the tables in my relationship. Make Ryan my househusband. Become a petulant genius whose work is seen as vital and is, therefore, too important to bother with dishes or busting up sibling squabbles.

“Of course that’s what you want,” my therapist sighed, “because that’s the power position.” And with that one remark, my ego was lanced.

One of the ideas that has blown my mind this year is C. Thi Nguyen’s idea of “value capture,” which I first learned about from this great essay by Tom Pendergast. To quote Tom:

“Basically, value capture happens when a person adopts the expressions of value offered by a system or social environment, expressions of value that are usually simplified and quantified, and allows those expressions to dominate their reasoning and motivations.”

Our struggle is between setting our own values or adopting the values of the system. Under our current form of late-stage capitalism, earning potential is the ultimate value. Capitalism rewards those with rare skills (like playing basketball real good or math smarts) or people who are adept at exploiting the system for profit (hedge fund managers, ruthless entrepreneurs.) But these are not necessarily the skills that families and communities actually need to thrive.

The pandemic exposed the lies of our valuation system by noting which workers were actually “essential”—and it wasn’t hedge fund managers. And while there have been union gains post-pandemic, there has, sadly, been no great revaluation of janitors over NBA players.

This skewed understanding of work’s value extends into families and relationships as well. Among full-time moms, it’s not uncommon to have partners who devalue their care work or say things like “you don’t get a vote in __ financial decision because you don’t earn any money.” This assumption of capitalist values turns what ought to be a partnership into a hierarchy where one partner holds power over the other.

This is tragic in part because it makes us lose sight of what people and communities actually need to thrive. We need good care for our children, the disabled, and the elderly. We need safe water, healthy food, a clean environment. We need neighbors who help and look out for each other. And yes, we need cars and computers and entertainment all the people who make them, but it’s a mistake to say that the work of a software engineer or a movie star is more valuable than that of a nanny or a janitor.

What we need is to wrest our values from the clutches of capitalism and reevaluate what success looks like for us and for our children. What if we started defining “success” by the strength of our community ties instead of our buying power? It would transform not only our lives, but our planet.

As for me, I am a work in progress. I feel proud of the community I’ve built. I love having time to write, to care for myself and my kids, and to serve my community, even if I don’t earn much. I would still love to write a bestseller, though.

Do you feel like a “success”? What would you need to have or do in order to consider yourself successful? Is your earning potential closely tied to your notion of “success”?

BONUS MATERIALS:

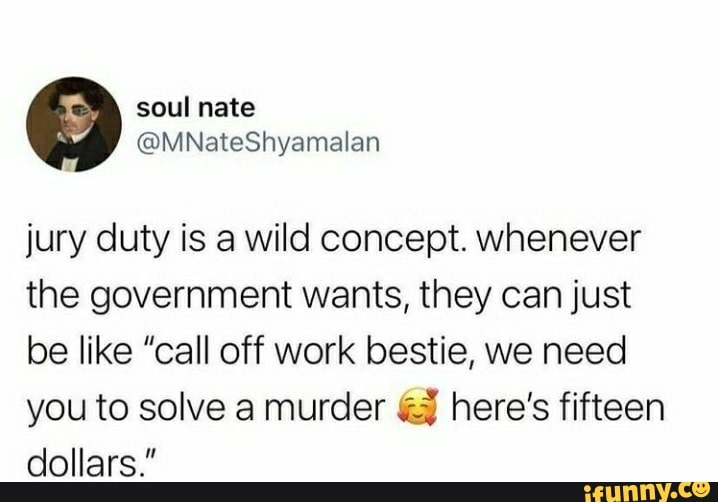

Since jury duty is an important but undervalued job, here’s my fav meme ever:

I struggle with this so much. I have worked hard my entire life, and I’m proud of what I’ve done. But I’ve never made the kind of money that would support a family. And because of that, the work I have done looks … cheap. Less meaningful. Add to that the fact that I never advocated for higher pay; I just trusted that my employers cared and were paying me market wages. And I was often wrong. (The exception was my short spell as a public school teacher, when a union assured I’d be paid a living wage. Not a pittance, as is popularly understood — it was a true middle-class income, with good benefits.) Now, nearing retirement, I’m faced with the accounting of what I’ve earned across my entire life, and it’s disheartening. I have to remind myself of what you’ve written here: those numbers are not my worth.

Earning a living in the arts and sciences (at least in academia) are probably the most precarious in our society. As a former physicist who also have musician friends, I found the financial outlook for artists and scientists to be very similar. There are very few positions available, the pay is awful, and there is no security unless one is among the top performers. And yet we love our professions to the point that we sacrifice all creature comforts in order to succeed. And then at some point, reality sets in and we either change to another more marketable field or we teach (I ended up doing both). In a free market economy, I am afraid that arts and sciences are considered to be a luxury. OK, I can accept that but what I find extremely frustrating is that certain professions which are of high value to society, e.g., primary/secondary school teachers, are still given very low pay-grades.