It’s been a month since I deleted my Twitter account and uninstalled both Instagram and Facebook. In some ways, it’s been a relief to not feel the constant need to “brand” and “market” myself online. In other ways, it’s been annoying—Facebook, despite its issues, continues to be the easiest way for me to share photos and updates with older relatives. In moments of boredom and stress, my thumbs were twitchy for the apps. I just wanted a quick laugh, a little meme pick-me-up.

Due to my volunteer work, I still had to log on a few times to manage a few social media pages, such as the one for the middle school PTA. And opening Facebook for this purpose quickly sidetracked me to scrolling, liking, and commenting on completely unrelated things. Which is not surprising, because that’s what the app is designed to do: as Chris Hayes points out in his latest book, The Siren’s Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource, these apps’ “infinite scroll” mimics a slot machine and is just as addictive.

The “sirens” of Hayes’ title allude to both the mythical singers who doomed sailors and the devices that bear their name. He draws on both as examples of our attention being harnessed against our will—one for noble purposes, the other nefariously. This is involuntary attention, and, alongside voluntary and social attention, make up the three types of attention. (An example of social attention is being able to pick your name out of a conversation you aren’t actively listening to—something apps harness via the “mentions” tab.)

Hayes’ work as a cable news host lends an interesting perspective to understanding attention. In the book, he details not only the dissatisfying nature of fame, but his personal struggle with the many bells and whistles that industry uses to ensnare viewers. He also brings in research from science, history, and philosophy to explore how attention works and how it’s currently being commodified and extracted by the attention economy—in particular, social media.

One of Hayes’ central points is that it’s much easier to grab attention than it is to keep it—think of how a loud noise is easier to attend to than a book. And social media capitalizes on this: Tiktok and adjacent video shorts rely mainly on quickly grabbing your attention, not on keeping it. I find this when I’m scrolling Facebook and come across “One Weird Trick”-type videos. The “trick” always turns out to be something completely obvious—i.e. did you know that if you want to get MORE PROTEIN, you should eat CHICKEN?!?!

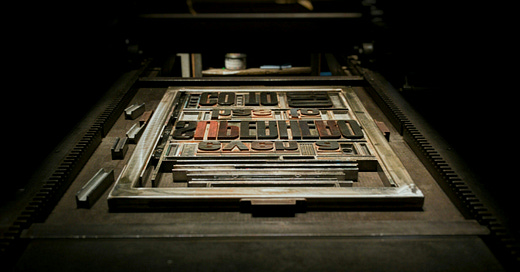

Humanity has lived through this kind of major technological disruption before when moveable type printing presses became widely available. Printing turned European medieval society on its head—information became more democratic and widely available, leading to scientific breakthroughs, improvements in literacy and education, and, oh yeah, the Protestant Reformation. But it wasn’t all good news: misinformation spread rapidly, too, including a popular witch-hunting manual. A recent study has shown that witch-hunting booms followed on the heels of new editions of this book, and that towns along trade routes (with more access to books) were more likely to host witch trials and execute supposed witches than more isolated towns.

Eventually, journalism developed as an institution, with standards and norms on things like sourcing and fact-checking. But while you can expect your local paper to follow rigorous standards, the internet is full of rogue detectives and “citizen journalists,” many of whom never let the truth get in the way of grabbing (and monetizing) attention. One particularly egregious example of this is true crime Tiktok, which regularly sees strangers spreading malicious gossip about supposed “suspects,” based on little-to-no evidence. This has led to real-life harassment, as in the case of a roommate of murder victims in Moscow, Idaho.

In fact, a well-known Jewish teaching holds that, “one who commits slander never gains forgiveness.” Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg explains it thusly in her book On Repentance and Repair: “…the damage is irrevocable—there’s no way for a penitent to correct their lie to all of the people who have heard it.”

So, speaking for social media we have PTA obligations, elderly relatives, and memes. On the other hand, we have an addictive slot machine that has the potential to create “unforgiveable” sin. Putting it that way, it seems like quitting social media is the good and right thing to do, yes?

Eh, maybe? As reader,

, pointed out, social media can be a lifeline for people with disabilities and chronic illness. I imagine this is the case for rural people, too. And in fact, at a training on militant nonviolent civil disobedience last week, our facilitator insisted that social media was as essential to the movement as lawyers and medics, because we can’t always trust the media to hold groups like the police accountable.So, what are we supposed to do?

This morning I read this fantastic post by Rose J. Percy and Benjamin Young, “Social Media: A Tool, not a Toy.” Young writes:

“I honestly think asking questions and processing communally is the answer. There is no one set way to navigate the world and era we’re born into. But— finding what works for us to live in harmony with all living presences and in alignment with our values, I think, requires asking hard questions that welcome vulnerability, authenticity, and truthfulness.”

Young and Percy engage thoughtfully with this social-media-as-tool metaphor as well as whether we are using or being used by these apps. I really recommend reading the whole post, it’s very thoughtful and nuanced.

One thing I’ve kept coming back to this month is the idea of epiphanies. While I love memes, they generally require little of me and are quickly forgotten. Epiphanies, on the other hand, require deep reflection. It’s mulling over a problem for days or weeks and finally coming to some sort of breakthrough, maybe while in the shower. Memes are fleeting; epiphanies have the power to change our entire perspective. Our attention is finite—there are only so many hours in a day. Does my love of memes and scrolling crowd out time I once spent in reflection?

The poet Mary Oliver had a great gift for attention. She composed her poems on long nature walks, even getting down on all fours to romp through the grass to gain an animal perspective. Earlier in the month, I shared The Summer Day from whence comes the famous quote, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do/ With your one wild and precious life?”

The answer, for Oliver, was neither scrolling Tiktok nor putting in more hours of “productive” activity; rather, it was watching a grasshopper. “I don't know exactly what a prayer is.” She writes. “I do know how to pay attention”.

This post has already commanded more of your attention than I usually do, but if you’ll permit me one more minute, I will share a poem I wrote inspired by Mary Oliver.

Attention is a Form of Love, or, The Impossible Journey

My son dawdles, plate in hand,

Between the table and dishwasher

Stopping, setting it down,

Oblivious to smears of ketchup

Or drying oatmeal.

He doesn’t think about the life of a plate

from counter to sink to neat stack

back to table, filling and emptying. It is not a race.

Why mind the dishes, once emptied?

In a few hours, more food, always beginning again

A parade of comestibles and their remnants.

Instead he is thinking of a turtle

Or a little hermit crab

How he would like to keep it cozy on his chest of drawers

To bid the shelled creature soft goodnights

Before closing his own eyes among the fluff

Adult attention is a spotlight,

(Or so the internet tells me)

Children are lanterns.

Theo’s light cascades over the table, pokes into the hidden world beneath it

This could be a fort, or a place to conceal a scare.

And what sound does this pot make?

And which spoon feels coldest on his face?

When will we have cookies again?

Does he have to take a bath?

And what book will we read once he’s pulled, sweet-smelling

From it?

And always on turtles.

I appreciate you wrestling with this subject. It’s one I’m wrestling with too.

I recently saw a reel (on FB, sorry!) in which a woman explained her conviction that capitalism is in its ending days. She believes that the thing that will eventually replace money is time. Time is something that everyone has, but it is a finite resource, immensely more valuable than the digital abstractions on which we currently base our wealth and economies. I’d never, ever thought of that. But I hope she’s right.

I like this, and especially the question of whether we're using social media or being used by it.